In the early 1880s, Congress took incremental steps to address the situation-investing in a few “New Steel Navy” ships-but as of Influence’s publication in 1890 the USN remained strikingly weak relative to the U.S. Oscar Wilde used USN weakness as a punch line for his comedy it was that obvious. Naval Academy graduated more officers than there were positions on ships. Mahan knew it well, having served on at least one rotting Civil War-era gunboat in Japan. Demobilization post-1865 had left the USN with a wooden-hulled “Old Steam Navy” that by the 1880s was literally rotting away. naval power lagged far behind that of its European peers, not to mention a handful of Latin America nations. New and expanding corporations had built industrial productivity to rival that of the North Atlantic “Great Powers.” Commercial interests increasingly looked overseas, eyeing opportunities in Latin American and East Asia, as well as the territorial infrastructure (the Panama Canal and coaling stations) necessary to exploit them.Īll the while-and strange as it sounds to twenty-first century readers long accustomed to post-1945 U.S. Consider the context: By the 1880s, railway lines knit together the United States continental empire from the Atlantic to the Pacific. economic power and the comparative weakness of the USN. The irony was chiefly with respect to the gap between growing U.S. Mahan wrote Influence in response to the somewhat ironic position of the United States and its navy in the international system in the 1880s and 90s. Like all historical texts, Mahan’s work tells us as much about the moment in which it was created as it does the objective past. Most importantly, however, it is an outline of a grand strategy bound up in a national turn toward the maritime world. As an analysis of purely naval strategy, it is also a thesis emphasizing concentrated battle fleet engagements as a means of achieving command of the sea.

In a narrow sense, Influence is a specific argument-a polemic-aimed at fin de siècle “navalists” about the necessity of expanding the United States Navy (USN). Like a piece of stained glass held up to the light, the Mahanian concept of “sea power” is many things at once, depending on one’s perspective. In doing so it encourages readers to consider the text through three lenses: polemic, naval strategy, and grand strategy. This essay leverages Mahan’s personal correspondence, archival sources, and an extensive body of commentary to explore the content, creation, and reception of Influence. True, the book is both of those things, but Mahan’s account of Atlantic imperial rivalries is also more valuably an “estimate of the effect of sea power upon the course of history and the prosperity of nations.” That form of comparative and nomological history makes Influence a strategic classic of enduring relevance. Many critics have read Influence as transparent propaganda for a domestic audience or a set of dated prescriptions about naval strategy.

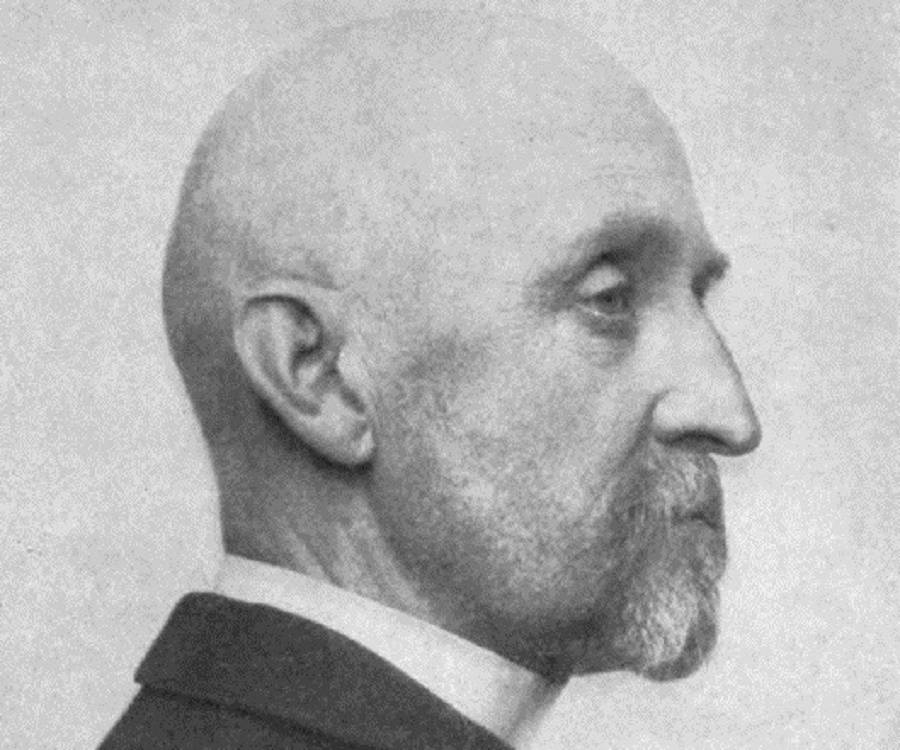

“sea power,” and a broader account of the relationships between the ocean, trade, and national strength. naval reform and expansion, Mahan’s research is at once a parochial argument about the need to revitalize U.S. Kennan’s 1947 “X Article” comes to mind as a comparable example. Indeed, it is likely true that no other piece of “applied history” has been as successful (for better or for worse) in the making and shaping of U.S. No book has had greater effect on the composition of and justification for industrial navies than Alfred Thayer Mahan’s 1890 The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)